The Credit Suisse CoCo Wipeout: Facts, Misperceptions, And Lessons For Financial Regulation

Learning Objectives

- Describe the features and mechanics of contingent convertible bonds (CoCos) and explain the rationale for banks to issue them.

- Explain the rescue of Credit Suisse by Swiss regulators in 2023 and compare it to the rescue of Bear Stearns by U.S. regulators during the financial crisis in 2008.

- Explain the rationale for the write-down of Credit Suisse CoCos that was engineered by regulators during the rescue of Credit Suisse and its takeover by UBS.

- Describe the reactions by market participants to the write-down of the CoCos, and explain and evaluate different arguments and lessons learned related to the decision to write down the CoCos.

- Video Lecture

- |

- PDFs

- |

- List of chapters

Features And Mechanics Of CoCos

- Contingent Convertible Bonds (CoCos) are specialized financial instruments used by banks primarily to enhance their capital structure and fulfill regulatory capital requirements, particularly under stress conditions. Their key features and mechanics are as follows:

- Loss Absorption: CoCos are designed to absorb losses when a bank’s capital level falls below a certain threshold. This absorption can be affected either through conversion of the bonds into equity or a write-down of the bond’s principal, depending on the specific terms of the CoCo.

- Triggers: CoCos include specific triggers that activate the conversion or write-down. These triggers are typically linked to the bank’s capital adequacy ratios, such as the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio.

- Mechanical Triggers: Activated when capital ratios fall below predefined levels.

- Discretionary Triggers (Point of Non-Viability, PONV): Allow regulators to initiate conversion based on their judgment of the bank’s financial health.

- Dual Role in Financial Stability: CoCos help stabilize a distressed issuer by providing immediate recapitalization, thus limiting the need for external capital injections such as government bailouts, which are costly and potentially increase moral hazard.

- Comparison with TLAC: Although similar to Total Loss Absorbing Capacity (TLAC) bonds in their function to protect equity and minimize systemic risk, CoCos are primarily designed to recapitalize going-concern banks (viable banks expecting to continue operations post-crisis), whereas TLAC bonds are intended to ensure that holding companies of globally significant banks can absorb losses and support operating affiliates during a resolution process.

- Trigger Mechanisms:

- Mechanical Trigger: Activated based on quantitative metrics like the capital-to-risk-weighted assets (RWAs) ratio.

- Discretionary Trigger: Activated based on a supervisory assessment of the bank’s solvency or the broader financial system’s stability.

- Loss Absorption Mechanisms:

- Equity Conversion: Converts bond into equity at a predefined rate, diluting existing shareholders but potentially avoiding further financial distress.

- Principal Write-Down: Reduces the bond’s principal, absorbing financial losses without converting to equity.

RATIONALE FOR BANKS TO ISSUE CoCos

- Regulatory Compliance and Capital Efficiency: CoCos help banks meet stringent regulatory capital requirements efficiently by providing a mechanism to enhance equity under stress without immediate dilution of existing shareholders. They are designed to act as a buffer to absorb shocks, thereby maintaining financial stability.

- Crisis Management: During financial distress, CoCos provide a pre-planned mechanism to bolster a bank’s equity base, enhancing financial stability and potentially averting broader financial crises. This feature is crucial for banks to quickly react to deteriorating financial conditions without needing external capital injections.

- Market Confidence: By issuing CoCos, banks can signal to the market their robustness in risk management and adherence to regulatory expectations, enhancing investor and stakeholder confidence. It shows that the bank is prepared to manage its risks while adhering to international banking standards.

- Investor Attraction: CoCos typically offer higher yields than traditional bonds due to their higher risk, attracting investors seeking higher returns in exchange for potential higher risk, including the risk of conversion under distressed conditions.

- Market Growth and Investor Impact: The CoCo market has expanded significantly, with issuances aimed at strengthening bank capital structures. While they provide high yields, the inherent risks and potential for conversion can affect market stability and investor returns, necessitating clear understanding and management of these instruments.

- Basel III Requirements:

- PONV Trigger: Under the Basel III framework, CoCos must include a Point of Non-Viability (PONV) trigger. This crucial mechanism determines when CoCos can convert into equity or be written down, activating only when the regulator determines that the bank has reached a point where it cannot continue without conversion or write-down. This helps ensure that the bank can be stabilized before it becomes insolvent, protecting the financial system and minimizing taxpayer interventions.

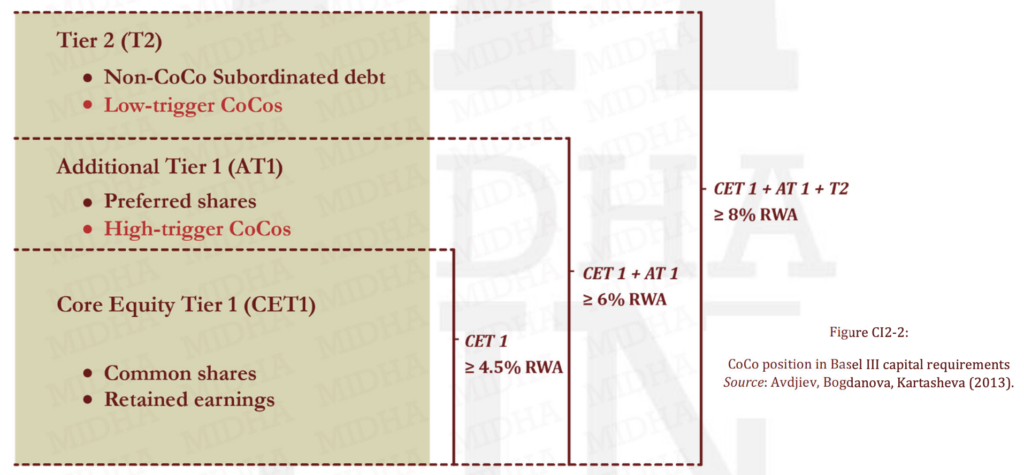

- Going-Concern Rule: CoCos must also meet the going-concern rule, which mandates a minimum trigger level of Core Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital relative to Risk-Weighted Assets (RWA). For Additional Tier 1 (AT1) instruments, this threshold is set at 5.125%. This rule ensures that the bank has enough capital to operate under normal and stressed conditions without becoming a burden on the financial system.

- Perpetual Nature: AT1 instruments are required to be perpetual, meaning they do not have a set maturity date. This allows the capital provided by these instruments to be considered stable and permanent from a regulatory perspective, enhancing the long-term resilience of the bank’s capital structure.

- Regulatory Capital Optimization: The structure of CoCos allows banks to optimize their regulatory capital. By issuing CoCos, banks can raise capital that qualifies under stringent regulatory frameworks for capital adequacy, such as Basel III, enhancing their ability to absorb losses in a structured and pre-planned manner.

In essence, CoCos are a critical tool for banks, allowing them to manage capital more flexibly and efficiently while providing a mechanism to address potential crises without immediate external assistance. They represent a sophisticated blend of debt and equity features, tailored to enhance financial stability and resilience.

Rescue Of Credit Suisse 2023 v Rescue Of Bear Stearns 2008

The rescue of Credit Suisse by Swiss regulators in 2023 and the rescue of Bear Stearns by U.S. regulators in 2008 provide two distinct approaches to averting financial collapse during times of severe stress in systemically important banks. Both interventions highlight the use of mergers with more stable financial institutions as a means to stabilize the distressed entities, but the methodologies and legal frameworks employed varied significantly due to different regulatory environments and the specific circumstances of each bank.

Rescue of Credit Suisse in 2023

- Background and Trigger: Following the global financial crisis of 2007-2008, regulatory reforms introduced CoCos as a tool to prevent the need for bailouts by enabling quick recapitalization of banks. Credit Suisse, exposed by the fallout from the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023, faced severe liquidity issues despite obtaining CHF 50 billion from the Swiss National Bank (SNB). This was inadequate to stabilize confidence, leading to continued deposit withdrawals.

- Regulatory Action: The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) and the SNB facilitated a takeover by UBS. On March 19, 2023, FINMA announced the complete write-down of Credit Suisse’s AT1 CoCos, a decision that surprised the market and was criticized for upsetting the traditional debt- equity claim hierarchy. This action was part of a broader strategy to merge Credit Suisse with UBS, aiming to stabilize the bank and prevent a larger financial crisis.

- Mechanism of Intervention: The write-down of CoCos directly bolstered Credit Suisse’s core capital, enabling a rapid de-leveraging of the bank’s balance sheet. This decision contrasted with traditional bailout methods, leaning instead on bail-in features designed to minimize taxpayer involvement and enforce market discipline.

- Outcome and Implications: While effective in preventing Credit Suisse’s collapse, the intervention led to significant losses for CoCo bondholders, with $17 billion written off, while shareholders retained about $3 billion in equity. This action reflected a shift toward enforcing creditor participation in crisis resolution costs, despite causing market unrest due to its unexpected nature. Rescue of Bear Stearns in 2008

- Background and Trigger: Bear Stearns faced a liquidity crisis in March 2008 due to its exposure to subprime mortgages, precipitating a rescue to prevent wider financial system disruption. The U.S. Federal Reserve and the Treasury orchestrated a merger with JPMorgan Chase under urgent circumstances.

- Regulatory Action: The Federal Reserve used Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act to provide emergency liquidity support and facilitate the merger. This included setting up a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to absorb troubled assets from Bear Stearns, initially persuading JPMorgan to purchase Bear Stearns at $2 per share, a price later increased to $10 after negotiations.

- Mechanism of Intervention: The creation of an SPV and the negotiation with JPMorgan involved significant public financial support and risk transfer, with the Fed and JPMorgan sharing the financial burden of stabilizing Bear Stearns.

- Outcome and Implications: The rescue temporarily stabilized financial markets but was criticized for setting a precedent that encouraged moral hazard. This approach highlighted the challenges of managing systemic risks without clear legal powers to force mergers or manage shareholder agreements effectively.

Comparative Analysis

- Regulatory Authority and Tools: Swiss regulators had more explicit legal authority to directly intervene in Credit Suisse’s operations, including the ability to enforce CoCos write-down without shareholder consent. In contrast, U.S. regulators in 2008 lacked direct power to enforce mergers, relying instead on emergency liquidity provisions and complex asset purchase agreements to stabilize Bear Stearns.

- Market Impact and Regulatory Tools: The Swiss intervention used a direct, predefined regulatory tool (CoCos) that clearly outlined the risks to bondholders, which, despite causing market surprise and criticism, was effective in quickly recapitalizing the bank. The U.S. intervention was more ad hoc, relying on public financial support and negotiations, which brought temporary stability but at the cost of potential long-term moral hazards.

- Investor and Market Reactions: The use of CoCos in Switzerland was a stark demonstration of modern financial regulation’s capacity to impose losses on investors to maintain systemic stability, reflecting a post- GFC shift towards requiring investor skin in the game. The Bear Stearns rescue, while successful in preventing immediate collapse, was heavily scrutinized for its impact on creating expectations of government bailouts in future crises.

These cases underscore the evolution of crisis management from reliance on public funds and complex negotiations to more streamlined, regulatory-driven interventions that prioritize financial stability while minimizing taxpayer exposure and enhancing market discipline.

Rationale For Write-Down Of Credit Suisse CoCos

The rationale for the write-down of Credit Suisse’s contingent convertible bonds (CoCos) during its 2023 rescue and takeover by UBS was a key part of the strategy to stabilize the bank without needing taxpayer- funded bailouts. This regulatory decision to reduce the value of CoCos aimed to quickly stabilize the bank, enforce accountability among investors, reduce the financial burden on taxpayers, and uphold the stability of the financial system. This approach represents a modern shift in financial regulation that utilizes inherent mechanisms within a bank’s capital structure to effectively manage crises.

- Regulatory Framework and Immediate Recapitalization

- Immediate Strengthening of Capital Base: The write-down of Credit Suisse’s CoCos was primarily aimed at immediately strengthening the bank’s capital base. By writing down the CoCos, regulators could quickly increase the bank’s core capital, which was essential for stabilizing its financial situation in the face of a severe liquidity crisis and ongoing deposit withdrawals.

- Minimizing Taxpayer Involvement

- Avoiding Public Financial Support: A fundamental goal of the CoCo mechanism is to avoid the need for taxpayer-funded bailouts. The CoCos are designed to absorb losses within the bank’s own capital structure by converting into equity or being written down before any public funds are put at risk. In the case of Credit Suisse, the complete write-down of CoCos effectively shifted the financial burden from taxpayers to CoCo investors, adhering to the post-2008 financial crisis regulatory ethos of “bail- in” versus “bailout”.

- Market Discipline and Investor Responsibility

- Avoiding Moral Hazard: By opting for a write-down rather than a bailout, Swiss regulators aimed to enforce market discipline and manage moral hazard. This decision reflected a strategic choice to ensure that financial institutions and their investors bear the consequences of their risk-taking, thus discouraging reckless behavior by signaling that rescue would not always come in the form of taxpayer money or government bailouts.

- Investor Impact: The direct financial impact on CoCo bondholders highlighted the inherent risks of these high-yield instruments. It served as a stark reminder to investors about the potential for losses, aligning with the regulatory intent that CoCos serve as a cushion during financial distress, absorbing losses to protect more senior creditors and depositors.

- Legal and Regulatory Authority

- Swiss Federal Powers: Unlike the more constrained authority of U.S. regulators during the 2008 financial crisis, the Swiss federal government, under Swiss emergency law, possessed extensive legal powers to manage financial crises directly. These powers included the authority to trigger the write- down of financial instruments such as CoCos. This significant authority allowed for quicker and more decisive action in stabilizing Credit Suisse without the need for complex arrangements like Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs).

- FINMA’s Role: The CoCo bond documents specifically provided the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) with the authority to trigger a conversion to equity or a write-down if Credit Suisse reached the Point of Non-Viability (PONV). In March 2023, when FINMA activated this mechanism, it facilitated an immediate recapitalization of the bank, enabling the CoCos to function as intended — as a financial buffer to absorb shocks and stabilize the bank’s capital structure without external capital injection.

- Protection of Financial System Stability

- Deleveraging the Balance Sheet: The write-down of CoCos, particularly the AT1 instruments, played a crucial role in quickly deleveraging Credit Suisse’s balance sheet. This action directly boosted the bank’s core capital at a critical time, enhancing its stability and financial viability as it merged with UBS.

- Systemic Stability: The swift intervention by Swiss authorities, facilitated by their broad legal powers, was crucial in maintaining confidence in the European banking system. By preventing the collapse of Credit Suisse through strategic use of built-in regulatory tools like CoCos, regulators not only stabilized the bank in question but also mitigated broader systemic risks that could have led to a wider financial crisis.

- Equity and Creditor Hierarchy

- Maintaining Creditor Hierarchy: While the write-down was a drastic measure, it adhered to the financial hierarchy where equity holders bear risks before debt holders. In this scenario, although CoCo holders suffered significant losses, the fundamental order of financial claims was intended to be respected, reinforcing the principle that higher returns (as offered by CoCos) come with higher risks.

- Final Outcome and Strategic Considerations

- Facilitation of the Takeover by UBS: The write-down of CoCos was also a strategic move to facilitate the takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS. By cleaning up Credit Suisse’s balance sheet and improving its capital ratios, the deal became more palatable to UBS and more likely to receive regulatory and market approval.

Market Reaction And Lessons

The write-down of Credit Suisse’s contingent convertible bonds (CoCos) in March 2023 triggered a variety of reactions from market participants and raised several arguments and lessons about the use of such financial instruments in managing banking crises.

Market Reactions

- Surprise and Discontent: The decision to write down the CoCos came as a surprise to many in the financial markets. Investors were particularly shocked because the CoCos were written off completely, leading to significant losses for CoCo bondholders, while shareholders retained substantial equity value. This unexpected move resulted in negative market reactions as it was seen as a deviation from the normal order of claims, where typically shareholders absorb losses before debt holders.

- Negative Commentary: The decision provoked a flood of negative market commentary, as it was perceived to have violated the established priority of claims. In financial hierarchies, equity holders are generally expected to bear losses before bondholders, and the treatment of CoCos contrasted with this principle.

- Regulatory Responses and Market Stability: The decision by Swiss regulators led several non-Swiss European regulatory bodies to publicly distance themselves from the Swiss government’s actions. Authorities such as the EU’s Single Resolution Board, the European Banking Authority (EBA), and the European Central Bank (ECB) made clear that in their jurisdictions, shareholders would absorb losses first before any AT1 capital is written down, a stance intended to prevent contagion and reassure the $250 billion European AT1 market.

- Legal Repercussions: The unexpected write-down and the perceived breach of the accepted creditor hierarchy prompted several lawsuits against Credit Suisse, arguing that FINMA’s intervention contradicted established financial norms and that the regulator did not act in good faith. Arguments and Lessons Learned

- Evaluation of Regulatory Decisions:

- Pro Argument: From a regulatory standpoint, the action taken by FINMA was within its legal rights and aligned with the intended purpose of CoCos—to absorb losses in times of financial distress without resorting to public bailouts. This was a proactive measure to stabilize the bank’s capital structure quickly and effectively, which is crucial in preventing a more extensive financial crisis.

- Con Argument: Critics argued that the decision undermined the trust of investors, particularly those in hybrid securities like CoCos. There was a concern that such actions could deter future investments in similar instruments, fearing abrupt and total losses. This could potentially increase the cost of capital for banks issuing such instruments, as investors demand higher returns to compensate for increased risks.

- Importance of Risk Assessment: It highlighted the necessity for investors to fully understand and assess the risks associated with complex financial instruments like CoCos. The high yields offered by such instruments are indicative of their high-risk nature, and the potential for total loss should be a key consideration in investment decisions.

- Understanding of Instrument Characteristics: The incident highlighted a significant gap in market understanding regarding CoCos, particularly the distinctions between going concern and gone concern CoCos, and their multiple triggers. This includes an automatic trigger related to the breach of the CET1 ratio and a discretionary trigger activated at the regulator’s assessment that the Point of Non-Viability (PONV) had been reached. The lack of clear criteria for determining the PONV contributed to this confusion.

- Regulatory Preparedness and Communication: There is a clear lesson about the need for better communication and preparedness on the part of regulators. While the regulatory actions were legally justified and aligned with the instruments’ purpose, the backlash suggests that the financial community could benefit from more detailed frameworks and guidelines on how such instruments are treated in crisis scenarios.

- Need for Regulatory Clarity and Simplified Structures: The market’s adverse reaction underscored the need for clearer regulatory guidelines and simpler CoCo structures. Investors faced pricing uncertainty, which likely increased the costs and risks associated with investing in CoCos. Proposals for reform suggest redesigning CoCos to exclude automatic or discretionary triggers and instead provide issuers with the option to convert debt into equity at a pre-specified strike price. This approach would simplify pricing based on established option pricing models and remove regulatory discretion in trigger activation, making CoCos more predictable and transparent.

- Countercyclical Benefits and Capital Management: The redesign would emphasize the countercyclical nature of CoCos, providing equity capital precisely when banks most need it. This helps stabilize the bank’s finances during downturns without the complexities and market shocks associated with current trigger mechanisms.