Margin (Collateral) And Settlement

Instructor Micky Midha

Updated On Learning Objectives

- Describe the rationale for collateral management.

- Describe the terms of a collateral and features of a credit support annex within the ISDA Master Agreement including threshold, initial margin, minimum transfer amount and rounding, haircuts, credit quality, and credit support amount.

- Describe the role of a valuation agent.

- Describe the mechanics of collateral and the types of collateral that are typically used.

- Explain the process for the reconciliation of collateral disputes.

- Explain the features of a collateralization agreement.

- Differentiate between a two-way and one-way CSA agreement and describe how collateral parameters can be linked to credit quality.

- Explain aspects of collateral including funding, rehypothecation and segregation.

- Explain how market risk, operational risk, and liquidity risk (including funding liquidity risk) can arise through collateralization.

- Describe the various regulatory capital requirements.

- Video Lecture

- |

- PDFs

- |

- List of chapters

Chapter Contents

- Terminology

- Rationale For Collateral Management

- Credit Support Annex (CSA)

- CSA Parameters – Threshold

- CSA Parameters – Initial Margin

- CSA Parameters – Minimum Transfer Amount

- CSA Parameters – Rounding

- CSA Parameters – Haircut

- CSA Parameters – Credit Quality

- CSA Parameters – Credit Support Amount

- Role of Valuation Agent

- Disputes and Reconciliation

- Margin Call Frequency

- Termination Features and Resets

- Coupons, Dividends and Remuneration

- Types of CSA

- Substitution

- Rehypothetication

- Segregation

- Collateralization Risks – Market Risk

- Collateralization Risks – Operational Risk

- Collateralization Risks – Legal Risk

- Collateralization Risks – Liquidity Risk

- Collateralization Risks – Funding Liquidity Risk

- Collateralization Risks – FX Risk

Terminology

- Historically, “collateral” has been a term used within OTC derivatives markets and contractual agreements such as ISDA Master Agreements. However, “margin” has been used in exchange-traded markets to represent a similar concept.

- The industry is generally converging on the use of the term margin over that of collateral.

- The term margin will, therefore, be used from now on, with occasional references to collateral and similar terms. The terms “collateralized” and “uncollateralized” will still be used to define the presence, or not, of margin in OTC derivatives.

Rationale For Collateral Management

- Margin represents a requirement to provide collateral in credit support or settlement. It supports a risk in a legally enforceable way.

- In exchange-traded markets, margin acts as a daily settlement of the value of a transaction. In OTC derivatives, basic idea of margining is that cash or securities are passed (with or without actual ownership changing) from one party to another as a means to reduce counterparty risk.

- A margin agreement reduces risk by specifying that margin must be posted by the party with negative exposure (or negative MtM ) to the other party to support such an exposure.

- To keep operational costs under control, posting of margin will not be continuous and will occur in blocks according to predefined rules.

- In the event of default, the non-defaulting party may seize the collateral and use it to offset any losses relating to the MtM of their portfolio.

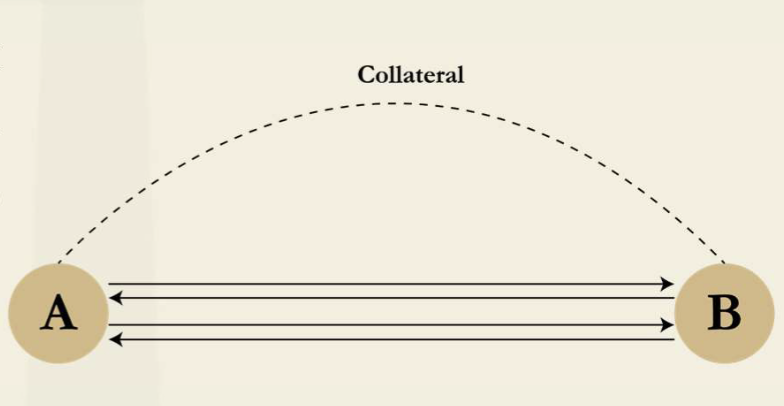

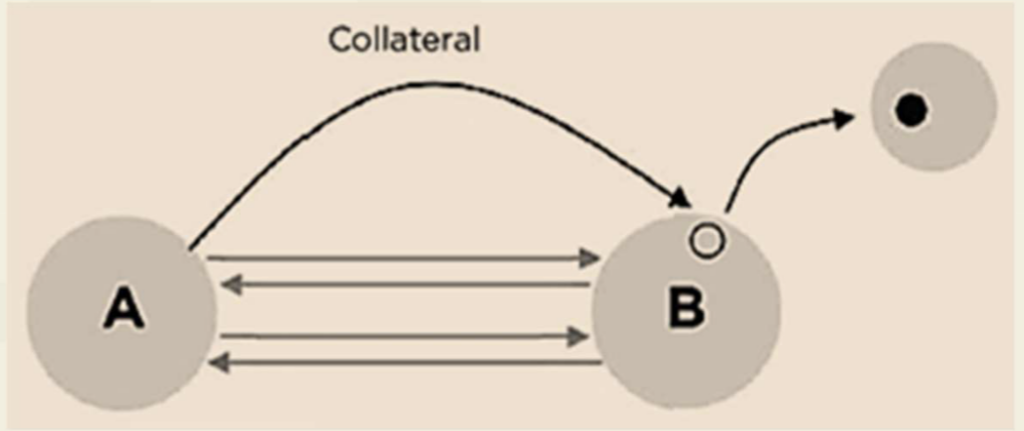

- The basic idea of margining is illustrated in this figure. Parties and have one or more derivative transactions between them and therefore agree that one or both of them will exchange margin in order to offset the exposure that will otherwise exist.

- Since margin agreements are often bilateral, collateral must be returned or posted in the opposite direction when exposure decreases. Hence, in the case of a positive , a party will call for collateral and in the case of a MtM negative they will be required to post collateral themselves.

- Posting margin and returning previously received margin are not materially very different. One exception is that when returning, a party may ask for specific securities back.

- Margin is bilateral mostly, but it can also be unilateral (where only one party has to post margin), especially when dealing with firms with excellent credit record.

- Collateral posted against OTC derivatives positions is, in most cases, under the control of the counterparty and may be liquidated immediately upon an event of default.

- To summarize, the main rationales for managing margin are –

- a) Reducing credit exposure – This gives the counterparties more assurance to initiate more trades, as counterparty credit risk is reduced.

- b) Providing the ability to trade with some counterparties – This can be applicable when a counterparty’s financial condition or credit rating does not allow it to participate in the uncollateralized derivative trades.

- c) Reducing regulatory capital requirements – The rules with respect to regulatory capital requirements are relaxed for collateralized exposures.

- d) Competitive pricing of counterparty risk – The provision for collateral helps in giving more competitive pricing of counterparty risk.

- Counterparty risk, in theory, can be completely neutralized as long as a sufficient amount of collateral is held against it. But there are legal obstacles, and issues such as rehypothecation. While collateral can be used to reduce counterparty risk, it gives rise to new risks, such as market, operational and liquidity.

Credit Support Annex (CSA)

- The Credit support annex, CSA , is a document that highlights the terms and conditions related to the margin in a derivatives contract. It permits the parties to mitigate their counterparty risk by agreeing to contractual margin posting. The Credit Support Annex (CSA) can be appended to the ISDA Master Agreement.

- The CSA typically covers the same range of transactions as included in the Master Agreement and it will be the net MtM of these transactions that will form the basis of margin requirements. However, within the CSA the parties can choose a number of key parameters and terms that will define the margin posting requirements (known as the “credit support amount”) in detail. These cover many different aspects such as –

- method and timings of the underlying valuations;

- the calculation of the amount of margin that will be posted;

- the mechanics and timing of margin transfers;

- eligible margin (currencies of cash and types of securities);

- margin substitutions;

- dispute resolution;

- remuneration of margin posted

- haircuts applied to margin securities;

- possible rehypothecation (reuse) of margin securities; and

- triggers that may change the margin conditions (for example, ratings downgrades that may lead to enhanced margin requirements)

- CSA parameters, which are also the components that make up the margin process are as follows –

- Threshold

- Initial margin

- Minimum transfer amount

- Rounding

- Haircut

- Credit quality

- Credit support amount

CSA Parameters – Threshold

- The threshold is the amount below which margin is not required, leading to under- collateralization.

- If the MtM is below the threshold then no collateral can be called and the underlying portfolio is therefore uncollateralised.

- If the MtM is above the threshold, only the incremental amount of collateral can be called for. (For example, a threshold of 5 and MtM of 8 would lead to collateral of 3 being required.)

- A threshold of zero means that collateral would be posted under any circumstance and a threshold of infinity is used to specify that a counterparty will not post collateral under any circumstance (as in a one-way CSA, for example). It is increasingly common to see zero thresholds for both parties since collateral agreements are as much about funding (FVA) and capital costs as well as pure counterparty risk issues (CVA) . The regulatory capital treatment of CVAs with nonzero thresholds also tends to be rather conservative.

- A non-zero threshold means that counterparties are willing to tolerate counterparty risk up to that level.

CSA Parameters – Initial Margin

- Initial margin is the opposite of a threshold and defines an amount of extra margin that must be posted independently of the of the underlying portfolio. An initial margin can be thought of as a negative threshold. For this reason, these terms are not seen together – either under collateralisation is specified via a threshold (with zero initial margin) or an initial margin defines over collateralisation (with a threshold of zero).

- It is usually required upfront at trade inception. The general aim of this is to provide the added safety of overcollateralisation to give a cushion against potential risks such as delays in receiving collateral and costs in the close-out process.

- Initial margin amounts change over time according to the perceived risk on the portfolio.

- Initial margin acts as a cushion against “gap risk”, the risk that the value of a portfolio may gap substantially in a short space of time.

- A risk-sensitive statistical estimation of initial margin may reference confidence levels of or more.

CSA Parameters – Minimum Transfer Amount

- A minimum transfer amount (MTA) is the smallest amount of margin that can be transferred. It is used to avoid the workload associated with a frequent transfer of insignificant amounts of (potentially non-cash) collateral.

- The size of the minimum transfer amount represents a balance between risk mitigation versus operational workload.

- The minimum transfer amount and threshold are additive in the sense that the MtM exposure must exceed the sum of the two before any margin can be called. This does not mean that the minimum transfer amount can be incorporated into the threshold.

CSA Parameters – Rounding

- A margin call or return amount may also be rounded to a multiple of a certain size to avoid dealing with awkward quantities. This is especially relevant when posting collateral in securities that by their nature cannot be divided infinitely like cash.

- This is typically a relatively small amount and will have a small effect on the impact of collateralisation.

- Minimum transfer amounts and rounding quantities are relevant for noncash margin where transfer of small amounts is problematic. In cases where cash-only margin is used (e.g. variation margin and central counterparties) then these terms are generally zero.

CSA Parameters – Haircut

- CSA allows each party to specify the assets they are comfortable accepting as margin and to define a “haircut” that allows for the price variability of each asset. The haircut is a reduction in the value of the asset to account for the fact that its price may fall between the last margin call and liquidation in the event of the counterparty’s default. As such, the haircut is theoretically driven by the volatility of the asset, and its liquidity, along with individual characteristics of the asset.

- Haircuts mean that extra margin must be posted, which acts as an overcollateralization. In practice, haircut levels are set when a CSA is negotiated and are not adjusted in line with changes in the market.

- Cash is the most common type of margin posted and may not attract haircuts. However, there may be haircuts applied to reflect the FX risk from receiving the margin in a currency other than the “termination” currency of the portfolio in question.

- Bonds posted as margin will have price volatility arising from interest rate and credit spread moves, although these will be relatively moderate (typically a few percent).

- Margin based on equity or commodity (e.g. gold) underlyings will clearly require much higher haircuts due to high price variability.

- The important points to consider in determining eligible margin and assigning haircuts are:

- time taken to liquidate the margin;

- volatility of the underlying market variable(s) defining the value of the margin;

- default risk of the asset;

- maturity of the asset;

- liquidity of the asset; and

- any relationship between the value of the margin and either the default of the counterparty or the underlying exposure (wrong-way risk).

- potential correlation between the exposure and the valuation of margin.

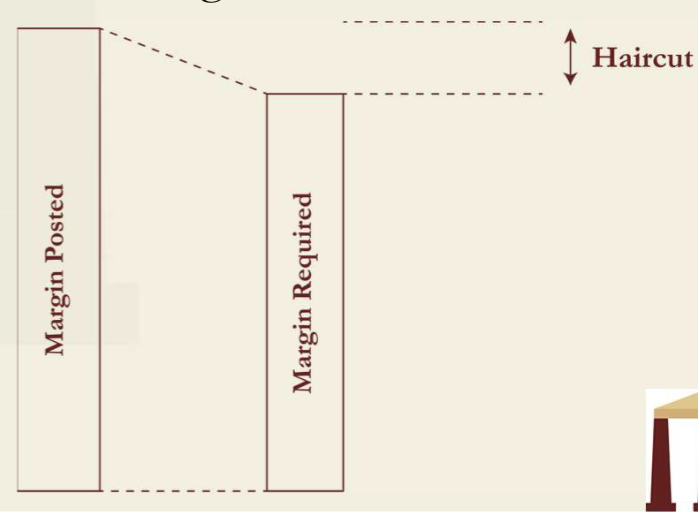

- A haircut of x% means that for every unit of that security posted as collateral, only (1 – x)% of credit (“valuation percentage”) will be given, as shown in the figure. The collateral giver must account for the haircut when posting collateral. For example, a haircut of 3%, means that only of the 97% credit (“valuation percentage”) will be given.

- For example, if a security attracts a haircut, and the margin call is $100,000. Then, the market value of margin has to be \(\frac{\$100,000}{1 – 0.05} \approx \$105,263\). Clearly, 95% of $105,263 is $100,000.

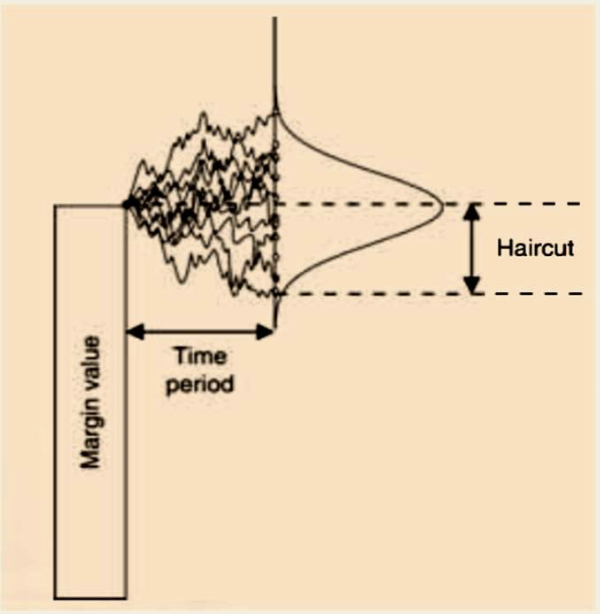

- Haircuts are typically defined as fixed percentage amounts, but they can be based on more dynamic amounts derived from a model. One way to derive a haircut would be to require that it covers a fairly severe potential worst-case drop in the value of the underlying asset during a given time period, as given in this figure. Under normal distribution assumptions, formula for haircut can be

\(haircut = \Phi^{-1}(\alpha) \times \sigma_m \times \sqrt{\tau}\)

where

\(\Phi^{-1}(\alpha)\) defines the number of standard deviations the haircut needs to cover involving the cumulative inverse normal distribution function and the confidence level \(\alpha\)(e.g. 99%).

\(\sigma_m\) is the volatility of the margin, and

\(\tau\) is the liquidation time

CSA Parameters – Credit Quality

- Thresholds, initial margin and minimum transfer amounts may all be linked to credit quality (usually in the form of ratings). The logic of this is clearly that margin becomes important as the credit quality of a counterparty deteriorates, and being able to take more margin (lower threshold and possibly an initial margin) more frequently (lower minimum transfer amount) is worthwhile.

- Rating triggers used to be viewed as useful risk mitigants but have been highlighted in the global financial crisis as being ineffective due to the slow reaction of credit ratings and the cliff-edge effects they produce. Hence, the above mentioned linkages to credit quality are becoming less common, especially considering that CSA terms are not changed frequently (they may not be renegotiated for many years).

CSA Parameters – Credit Support Amount

- ISDA CSA documentation defines the “credit support amount” as the amount of margin that may be requested at a given point in time. The parameters in a typical CSA may not aim for a continuous posting of margin due to the operational cost and liquidity requirements. The threshold and minimum transfer amount discussed above serve this purpose.

- If the MtM of the portfolio minus the threshold is positive from either party’s view, then they may be able to call margin subject to the minimum transfer amount.

Role of Valuation Agent

- The valuation agent is normally the party calling for the delivery or return of margin and thus must handle all calculations. Large counterparties trading with smaller counterparties may insist on being valuation agents for all purposes. In such a case, the “smaller” counterparty is not obligated to return or post margin if they do not receive the expected notification, while the valuation agent may be under obligation to make returns where relevant. Alternatively, both counterparties may be the valuation agent and each will call for (return of) margin when they have an exposure (less negative MTM ). In these situations, the potential for collateral disputes is significant.

- The role of the valuation agent is to calculate –

- current MtM, including the impact of netting;

- the market value of margin previously posted and adjust this by the relevant haircuts;

- the total uncollateralised exposure; and

- the credit support amount (the amount of margin to be posted by either counterparty.

Disputes and Reconciliation

- A dispute over a collateral call is common and can arise due to one or more of a number of factors:

- trade population;

- trade valuation methodology;

- application of CSA rules (e.g. thresholds and eligible collateral);

- market data and market close time;

- valuation of previously posted collateral.

- For centrally-cleared transactions, margin disputes are not relevant since the CCP is the valuation agent.

- In bilateral markets, reconciliations aim to minimise the chance of a dispute by agreeing on valuation and margin requirements across portfolios. The frequency of reconciliations is increasing; for example, ISDA (2015) notes that most portfolios – especially large ones – are reconciled on a daily basis. Margin management practices are being continually improved.

Margin Call Frequency

- Margin call frequency refers to the periodic timescale with which margin may be called and returned. (mail to be sent to GARP, frequency and time are opposite)

- A longer margin call frequency may be agreed upon, most probably to reduce operational workload and in order for the relevant valuations to be carried out. Some smaller institutions may struggle with the operational and funding requirements in relation to the daily margin calls required by larger counterparties.

- While a margin call frequency longer than daily might be practical for asset classes and markets that are not so volatile, daily calls have become standard in most OTC derivatives markets. Furthermore, intraday margin calls are common for more vanilla and standard products such as repos and for derivatives cleared via CCPsv.

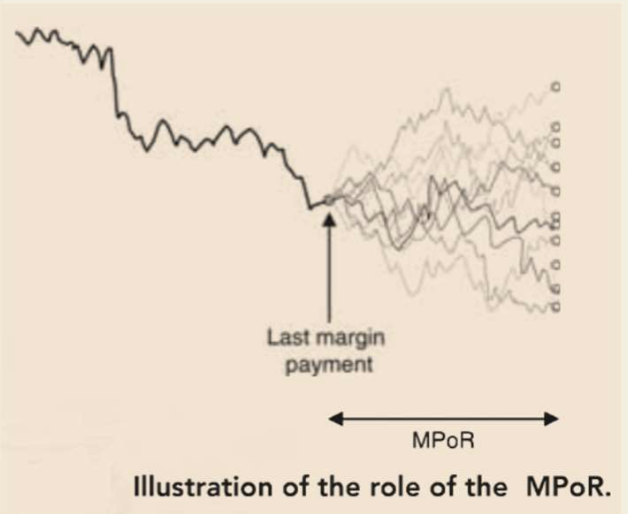

- Margin call frequency is not the same as the MPoR. The MPoR represents the effective delay in receiving margin that should be considered in the event of a counterparty default. The margin call frequency is one component of this, but there are other considerations also. It could, therefore, be that the margin call frequency is daily, but the MPoR is assumed to be 10 days.

Termination Features and Resets

- In practice, there are two methods of margin transfer –

- Security interest – In this case, the margin does not change hands but the receiving party acquires an ownership interest in the margin assets and can use them only under certain contractually defined events (e.g. default). Other than this, the margin giver generally continues to own the securities.

- Title transfer – Here, legal possession of margin changes hands and the underlying margin assets (or cash) are transferred outright but with potential restrictions on their usage. Aside from any such restrictions, the margin holder can generally use the assets freely and the enforceability is therefore stronger.

- Title transfer is more beneficial for the margin receiver since they hold the physical assets and are less exposed to any issues such as legal risk.

- Security interest is more preferable for the margin giver since they still hold the collateral assets and are less exposed to problems such as overcollateralization if the collateral receiver defaults.

Coupons, Dividends and Remuneration

- As long as the giver of margin is not in default, they remain the owner from an economic point of view. Hence, the receiver of margin must pass on coupon payments, dividends and any other cashflows. One exception to this rule is in the case where an immediate margin call would be triggered. In this case, the collateral receiver may typically keep the minimum component of the cashflow (e.g. coupon on a bond) in order to remain appropriately collateralised.

- The margin agreement will also stipulate the rate of interest to be paid on cash and when interest is to be transferred between parties. Interest will typically be paid on cash collateral at the overnight indexed swap (OIS) rate. However, OIS is not necessarily the most appropriate margin rate, especially for long-dated OTC derivatives where collateral may need to be posted in substantial amounts for a long period. This may lead to a negative ‘carry’ problem due to a party funding the collateral posted at a rate significantly higher than the OIS rate they receive. This is one source of FVA.

- Where there is optionality in a margin agreement (e.g. the choice of different currencies of cash and/or different securities), this may be quantified via collateral funding adjustment (ColVA).

Types of CSA

- No CSA– In some OTC derivatives trading relationships, CSAs are not used because one or both parties cannot commit to margin posting. A typical example of this is the relationship between a bank and a corporate where the latter’s inability to post margin means that a CSA is not usually in place (for example, a corporate treasury department may find it very difficult to manage their liquidity needs under a CSA).

- Two-way CSA– A two-way CSA is more typical for two financial counterparties, where both parties agree to post collateral. Two-way CSAs with low thresholds are standard in the interbank market and aim to be beneficial to both parties.

- One-way CSA- A one-way CSA is used where only one party can receive collateral. This actually represents additional risk for the collateral giver and puts them in a worse situation than if they were in a no-CSA relationship. A typical example is a high quality entity such as a triple-A sovereign or supranational trading with a bank. Banks themselves have typically been able to demand one-way CSAs in their favour when transacting with some hedge funds. The consideration of funding and capital costs have made such agreements particularly problematic in recent years.

Substitution

- Sometimes a party may require or want margin securities returned. This may due to

- operational reasons (for example, they require the securities for some reason), or

- optimisation reasons.

- In such cases, it is possible to make a substitution request to exchange an alternative amount of eligible margin (with the relevant haircut applied).

- Generally, substitution may only be allowed if the holder of the margin gives consent.

- If consent is not required for the substitution then such a request cannot be refused (unless the margin type is not admissible under the agreement), although the requested margin does not need to be released until the alternative margin has been received.

Rehypothetication

- Another aspect in relation to funding efficiencies is the reuse of margin. For margin to provide benefit against funding costs, it must be re-usable. While cash margin and margin posted under title transfer are intrinsically reusable, other margin must have the right of rehypothecation, which means it can be used by the margin holder (for example, in another collateral agreement or a repo transaction).

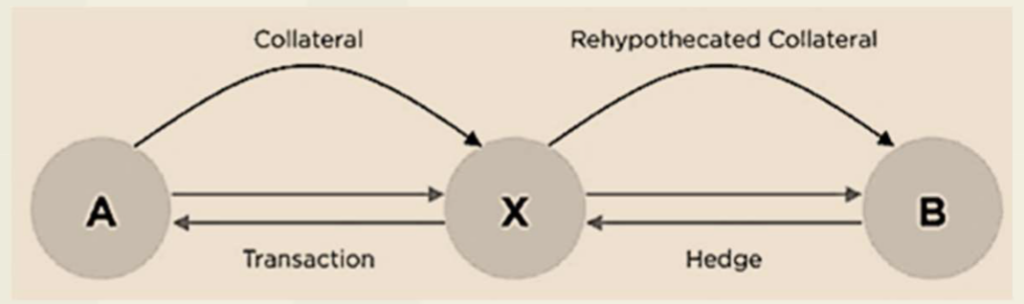

- Due to the nature of the OTC derivatives market, where intermediaries such as banks generally hedge transactions, margin reuse is natural, as illustrated in this figure.

- Rehypothecation can allow a smooth flow of margin through a system without creating additionalliquidityproblems,butitmaycreateanotherkindofriskbecauseof interdependent relationships inside the system.

- From the point of view of funding, rehypothecation is important. However, from the point of view of counterparty risk, rehypothecation is dangerous since it creates the possibility that rehypothecated collateral will not be received in a default scenario. So, rehypothecation may reduce funding liquidity risk but increase counterparty risk. In some cases, rehypothecation may result in a “loss of control” over the collateral.

- Before the global financial crisis, the rehypothecation of collateral was common and was viewed as a critical feature. However, bankruptcies such as Lehman Brothers and MF Global illustrated the potential problems where rehypothecated assets were not returned. One example is that customers of Lehman Brothers Inc. (US) were treated more favourably than the UK customers of Lehman Brothers International (Europe) in terms of the return of rehypothecated assets (due to differences in customer protection between the UK and the US). There has been a significant drop in rehypothecation in the aftermath of the crisis. This is safer from the point of view of counterparty risk but creates higher funding costs.

Segregation

- Even if collateral is not rehypothecated, there is a risk that it may not be retrieved in a default scenario. Segregation of collateral is designed to reduce counterparty risk and entails collateral posted being legally protected in the event that the receiving counterparty becomes insolvent. In practice, this can be achieved either through legal rules that ensure the return of any collateral not required (in priority over any bankruptcy rules), or alternatively by a third party custodian holding the initial margin.

- Segregation is therefore contrary and incompatible with the practice of rehypothecation, and hence cannot happen together.

- The basic concept of segregation is illustrated in this figure.

Collateralization Risks – Market Risk

- Market risk is the risk of changing of market levels occurring after collateral is posted. For example, the value of the collateral may reduce to such an extent that even active haircuts won’t be able to offset the entire loss. Residual risk can exist under the margin agreement due to contractual parameters such as thresholds and minimum transfer amounts that effectively delay the margin process. This is a market risk as it is defined by market movements since the counterparty last posted margin.

- Another important aspect is the inherent delay in receiving collateral. The margin period of risk (MPoR) is the term used to refer to the effective time between a counterparty ceasing to post margin and when all the underlying transactions have been successfully closed-out and replaced (or otherwise hedged), as illustrated in this figure. Such a period is crucial since it defines the effective length of time without receiving margin where any increase in exposure (including close-out costs) will remain uncollateralised. Note that the MPoR is a counterparty risk specific concept (since it is related to default) and is not relevant when assessing funding costs.

- In general, it is useful to define the MPoR as the combination of two periods:

- Pre-default – This represents the time prior to the counterparty being in default and includes the following components –

- Valuation and margin call.

- Receiving collateral.

- Settlement.

- Grace period

- Post-default – This represents the process after the counterparty is contractually in default and the closeout process can begin and includes the following components –

- Macro-hedging

- Close-out of transactions.

- Rehedging and replacement.

- Liquidation of assets.

- Pre-default – This represents the time prior to the counterparty being in default and includes the following components –

- Market risk might be relatively small in comparison to the risk of an uncollateralized scenario, but it is difficult to quantify and hedge against. This risk may not lead to an immediate actual loss, but it creates significant exposure for the margin holder, leading to loss in case of default.

Collateralization Risks – Operational Risk

- The time-consuming and intensely dynamic nature of collateralisation means that operational risk is a very important aspect. The following are examples of specific operational risks –

- missed collateral calls

- failed deliveries

- computer/human errors

- Operational risk can be especially significant for the largest banks that may have thousands of relatively non-standardised collateral agreements with clients, requiring posting and receipt of billions of dollars of collateral on a given day. This creates large operational costs in terms of aspects such as manpower and technology.

- Basel III recognizes operational risk in such situations by requiring a larger MPoR to be used in some cases (e.g. where the number of transactions exceeds 5,000, or the portfolio contains illiquid margin or exotic transactions that cannot easily be valued under stressed market conditions). A history of margin call disputes also requires a larger MPoR to be used. Larger MPoRs lead to higher capital requirements and therefore produce an incentive for reducing operational risk.

Collateralization Risks – Legal Risk

- Receiving margin also involves some legal risk in case there is a challenge to the ability to net margin against the value of a portfolio or over the correct valuation of this portfolio. In major bankruptcies this can be an important consideration, such as the case between Citigroup and Lehman Brothers.

- Rehypothecation and segregation are subject to possible legal risks. Holding margin gives rise to legal risk in that the non-defaulting party must be confident that the margin held is free from legal challenge by the administrator of their defaulted counterparty.

- In the case of MF Global, a major derivatives player, segregation was not effective and customers lost money as a result. This raises questions about the enforcement of segregation, especially in times of stress. Note that the extreme actions from senior members of MF Global in using segregated customer collaterals were caused by desperation to avoid bankruptcy. It is perhaps not surprising that in the face of such a possibility, extreme and even illegal actions may be taken. There is obviously the need to have very clear and enforceable rules on collateral segregation.

Collateralization Risks – Liquidity Risk

- Holding margin creates liquidity risk in the event that collateral has to be liquidated (sold) following the default of a counterparty. In such a case, the non-defaulting party faces transaction costs (e.g. bid-offer) and market volatility over the liquidation period when selling collateral securities for cash needed to re-hedge their derivatives transactions. This risk can be minimised by setting appropriate haircuts to provide a buffer against prices falling between the counterparty defaulting and the party being able to sell the securities in the market.

- There is also the risk that by liquidating an amount of a security that is large compared with the volume traded in that security, the price will be driven down and a potentially larger loss (well beyond the haircut) incurred. If a party chooses to liquidate the position more slowly in small blocks, then there is exposure to market volatility for a longer period.

- A link between the value of the margin and the counterparty’s credit quality leads to wrong-way risk which exacerbates the issue of liquidity risk.

- The above liquidity considerations only come into play when a counterparty has actually defaulted.

Collateralization Risks – Funding Liquidity Risk

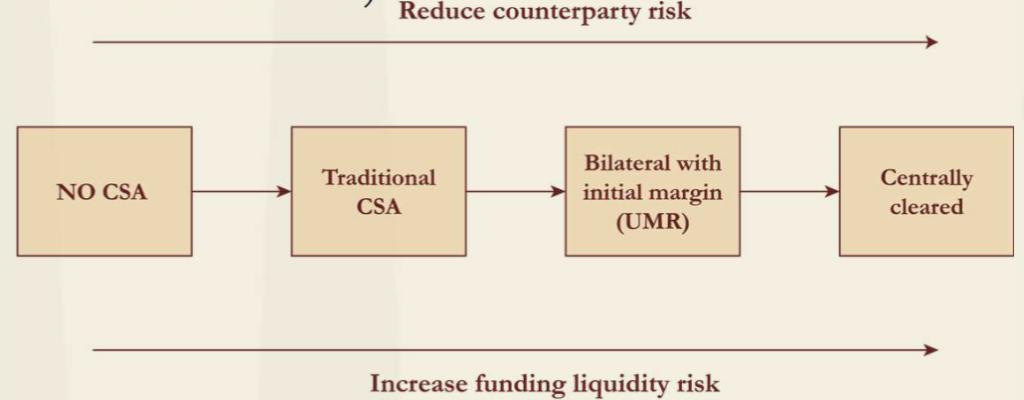

- Collateralization may reduce counterparty risk, but it increases funding liquidity risk. Funding liquidity risk, in this case, is defined as the potential risk arising from the difficulty to raise required funding in the future, especially when margin needs to be segregated and/or cannot be rehypothecated. Margin agreements clearly create such risk as they require contractual margin payments over short timescales, with the magnitude of these payments typically not being deterministic (since it is related to the future value of transactions).

- At a high level, the move to more intensive margin regimes can be seen as reducing counterparty risk at the expense of increasing funding liquidity risk.

- Margin converts counterparty risk into funding liquidity risk. This conversion may be beneficial in normal, liquid markets where funding costs are low. However, in abnormal markets where liquidity is poor, funding costs can become significant and may put extreme pressure on a party.

Collateralization Risks – FX Risk

- If margin is posted in foreign currency, then its value will be susceptible to fluctuations in the exchange rates. The risk arising from these fluctuations should be hedged using forwards/ futures, and it should be done carefully so that it does not lead to additional risks for the institution.